ARTWALK

For decades women have been struggling against inequality and oppression. Although grasping success from it was not nearly impossible, the battle was still far from ending. As women are still disproportionally suffering from all forms of violence and discrimination in every aspect of life. With this said, advocacies and protest movements for women’s issues were raised. Which are collectively termed feminism. A women’s movement that comprises forces from not only women but also men who work and fight against gender equality to improve the lives of women as a social group. Primarily this movement aims to cease sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression to finally achieve extensive gender equality both in laws and in reality.

Feminism, as a full realization of activism, is an interdisciplinary approach towards inequality and injustice issues coming from a conventionalist viewpoint of constructing gender and sexuality. It aims to interrogate and to effect change in inequities created by intersectional grids in ability, class, race, gender, sex, and sexuality. This urge to reform has reached towards the creation of feminist art, not only to express the movement in a different way of evoking perceptions that words simply could not accomplish. But also, to rewrite the male-dominated art history, change the contemporary world through art forms, and create opportunities previously unavailable for women and minority artists. It has opened doors for the identities of women alongside activist art genres not only in the field of art but also in the general overview of societies.

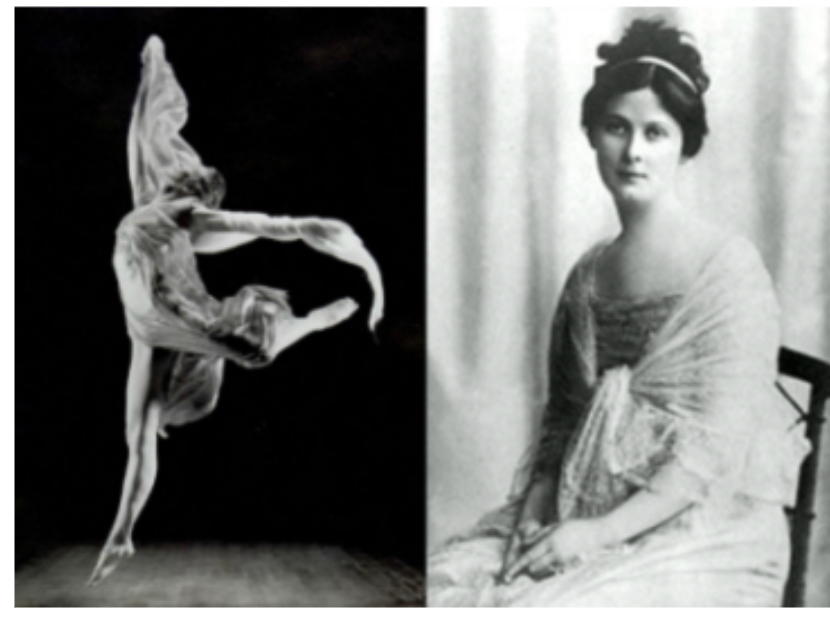

“Modern Dance” by Angela Isadora Duncan

Dance is an everchanging and dynamic movement -so is feminism. The ideals of feminism converged over time and the struggles were confronted and surpassed. However, there are still many inequalities that have yet to be addressed. Art, as one of the most powerful drivers of radical change in society, has significantly influenced the progression and development of feminism over time. It must be noted that modern dance choreographers were of great help in shaping modern dance that was intertwined with feminism, particularly, Isadora Duncan, the mother of Modern dance and a pioneer of feminism.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, European ballet was becoming more famous in different parts of the United States of America. Isadora Duncan, an American dancer who is considered as the mother of modern dance, reconstructed and influenced the subsequent evolution in the concept and essence of classical ballet through her innovation of ‘free movement’ and pioneered the idea of natural movement and dancing barefooted. Her teachings and performances during her time helped set liberation in the genre of ballet from its conservative restrictions and paved the development of modern dance. She was renowned as one of the first dancers to perform the interpretive dance in the status of creative art.

She started dancing in the theater in 1896. By 1899, she moved to London to expand her artistry. In this new country as well was where she fell in love with Greek culture/art. In 1902. She joined the company of Loie Fuller which took her around Europe while creating and performing her own dance techniques. In 1905, she opened her first dance school in Gruenwald, where she opted to not teach children to imitate her movements but to create their own. She was also able to train a group of dancers who became, later on, her performing company known as, “The Isadorables”. In 1908, she continued her tours in the United States where at first, she encountered difficulties because music critics did not believe that a dancer could interpret music. From 1909 onwards, she became a prominent modern dancer across the globe. Lastly, by the 1920s, Isadora had decided to end her dancing career.

Isadora and her family were poverty stricken during her childhood, hence, she and her sister (Elizabeth), started teaching dance classes to local children at the age of 6 to earn extra money. She taught other children by means of improvising any dance movements that came to her head, which she thought was pretty. She also took ballet lessons, but at 9 years old, she discontinued because she saw and felt like ballet was an “articulated puppet…producing artificial mechanical movement not worthy of the soul” (Duncan 61). This was primarily her driving force for pioneering the concept of natural movement, dancing barefooted, and dressing in short white tunics in contrast to the restrictive and rigid disciplined nature of ballet. In addition, this courageous movement shocked the conservative society at that time, who mandated women to dress and act ‘modestly’. This childhood scenario was her inspiration to begin a bold movement of choreographing for the female body and spearheading a free and liberating fashion for women –at a time when womanhood was dictated to be lived conservatively and demurely.

As a person who is genuinely passionate about dancing, her art inspired me. She was able to fuel my passion and inspire me to appreciate the art of dancing more, as a way of expressing ourselves and not only for mere entertainment. I chose her, and her art because she was able to use her passion in expressing herself and fearlessly enduring the criticisms that the traditionalist and conservative society tends to frown upon. In addition, she was able to fight off the ‘modest’ concept and mentality in fashion for women in society by stripping off corsets and removing their shoes. This way allowed the female body to be liberated from the long-running prohibitions of societal norms and restrictions, and instead, spearheaded the celebration of female identity. She and her dancers also dressed themselves in short white tunics to allow and emphasize free movements, form, and dance as art for expression. Over and above, her goal of eliminating the controlled vision of females and their bodies, eradicating prior stereotypical mindsets and restrictions, and allowing women to develop a newly established sense of freedom where they can express themselves best, whether it may be in fashion, actions, or in dancing. Duncan, in every way, was a great modernist of her time, significantly influencing a cultural shift towards a more radical form of expressing one’s self, despite being strongly criticized at first because of her costumes and concepts that emphasized the female figure who wished to break free from the old and dictating standards of society.

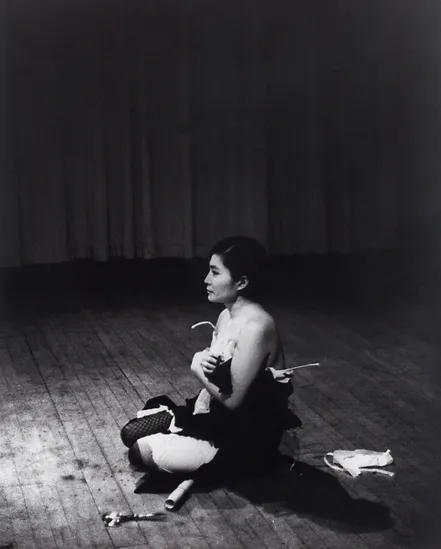

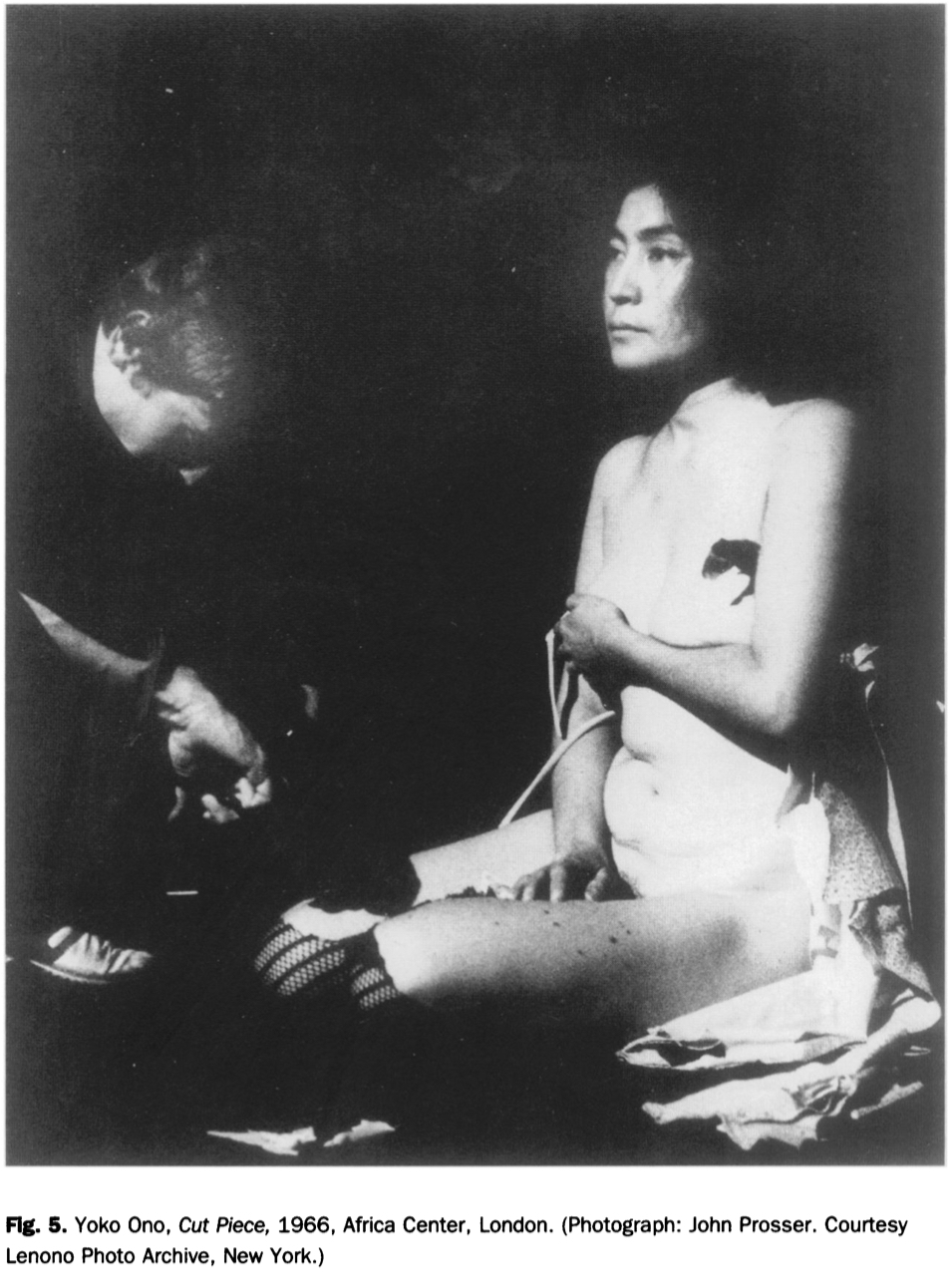

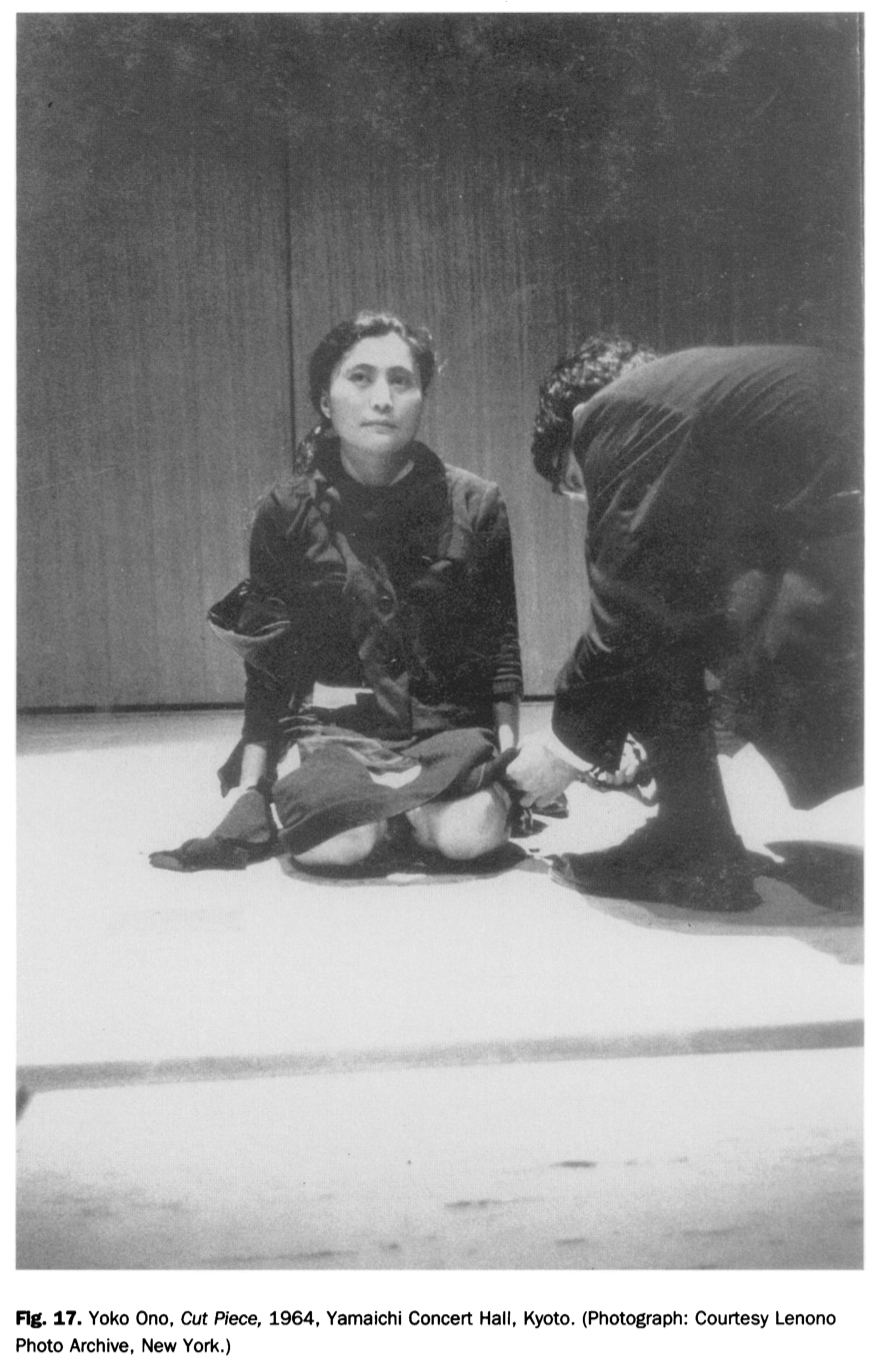

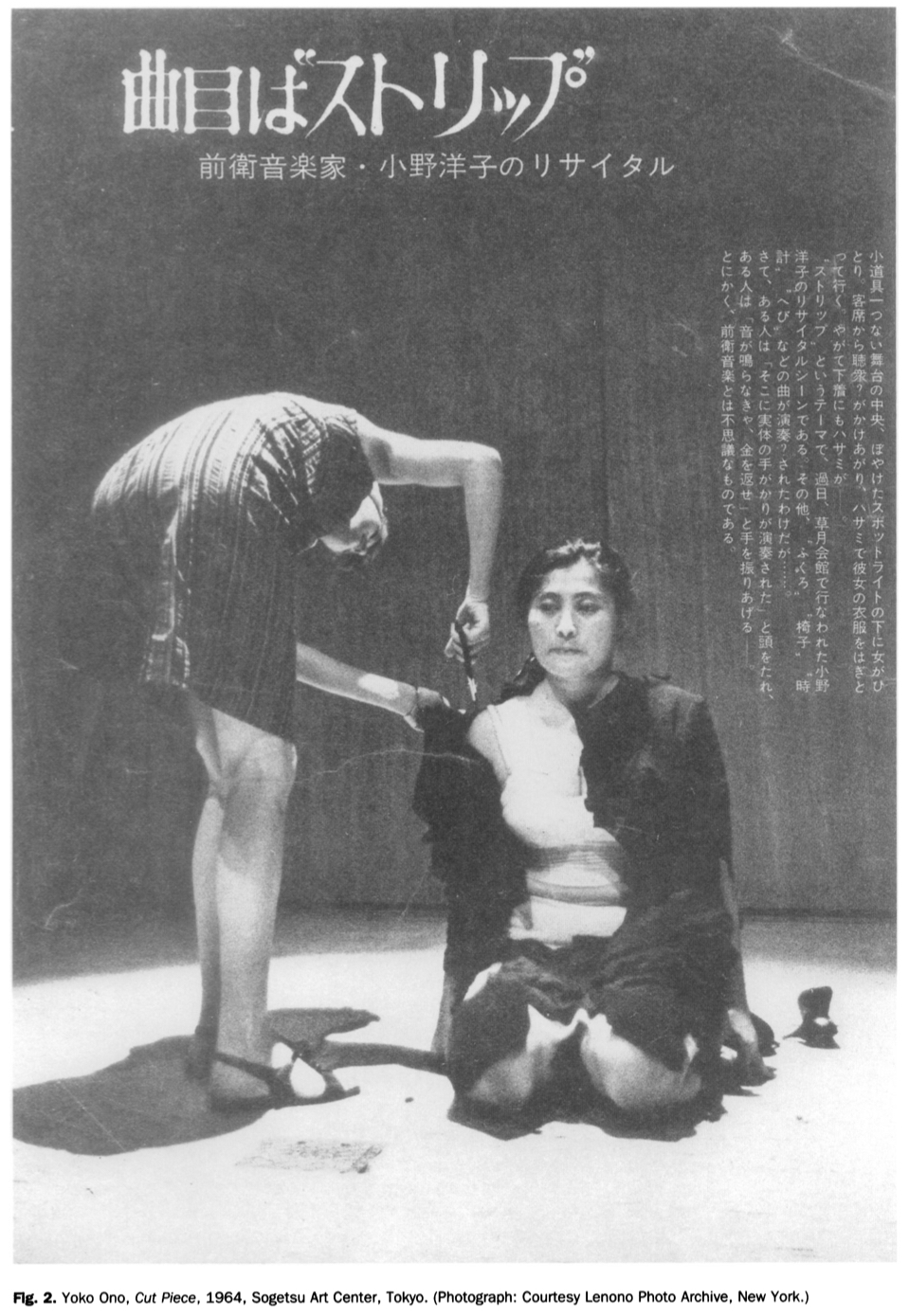

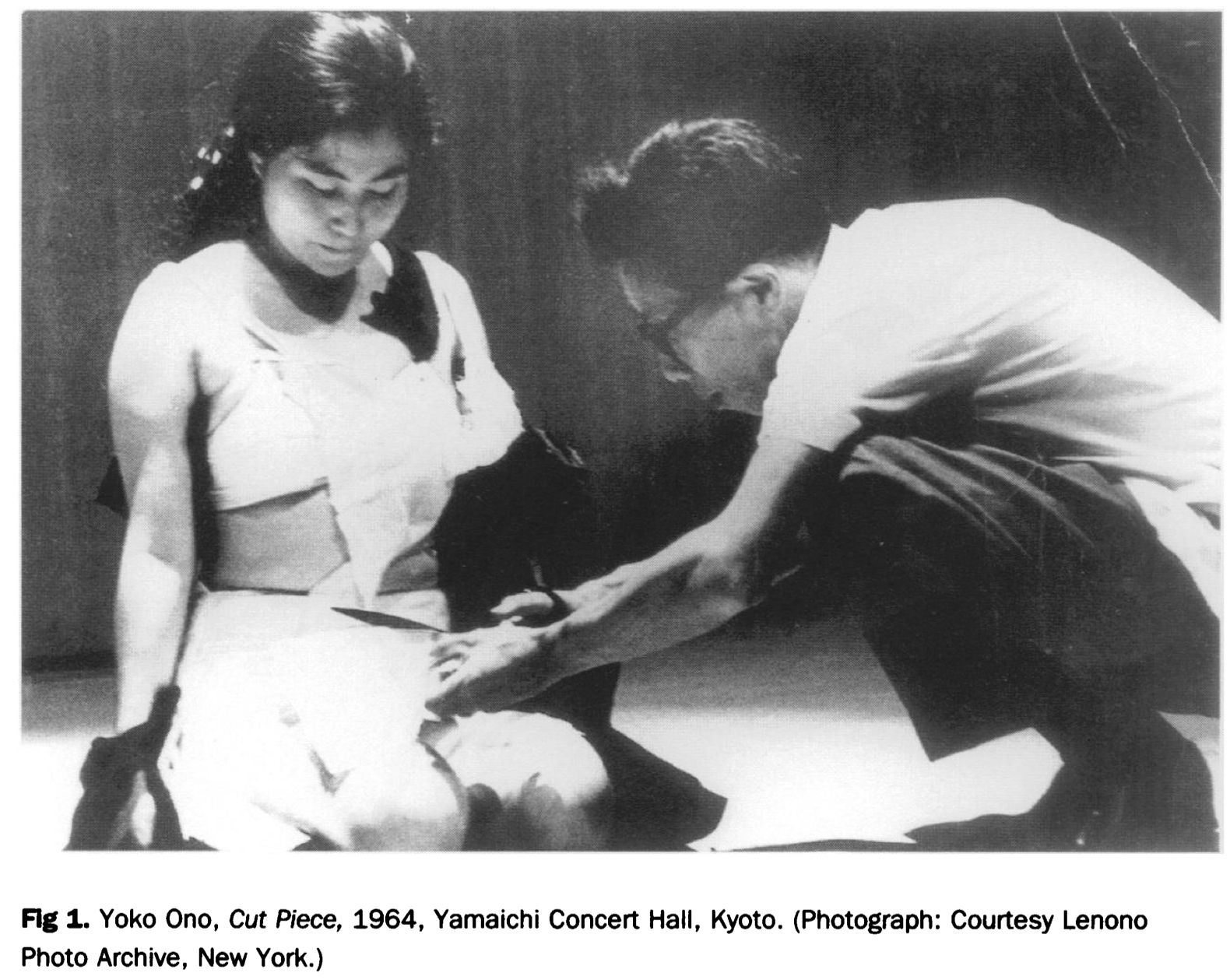

“Cut Pieces” performed by Yoko Ono

This piece debuted in Tokyo in 1964 and was later on performed as well at least four more times in Japan, London, and the United States. During the performance, Ono would just kneel on the stage with a pair of scissors in front of her and then would just explain the outline of the parameters of the performance. That the audience are allowed to come on stage and cut off any piece of her clothing and take it as a souvenir from the performance. The performance will end when finally Ono decides to conclude it. During her first performance, the audience were blatantly hesitant to cut pieces of her shirt or skirt. However, as it proceeded, the audience became bolder and even came to the point where her undergarments were cut, which prompted Ono to bring her hands up and cover her body. This performance, being considered one of the earliest examples of Performance Art in history, addresses the issue of sexual violence and embodies the passive objectification of women in society. Moreover, the performance portrayed the following themes: feminism, materialism, gender, class, and cultural identity.

The artist behind the masterpiece “Cut Piece” was Yoko Ono, a female Japanese artist that is prominent in her multimedia performances, songwriting, and peace activism. She was well-known for having one of the strongest feminist voices to emerge from the world of art in the 1960s. She is also associated with John Lennon since she is his second wife. Although she may be remembered because of her relationship with The Beatles star, she outshined this with the fact that she was able to push the boundaries of performance art, specifically her daring art, “Cut Piece,” which became famous in 1964. This work of art was highly influential since it sparked the need for social change in her audiences.

Yoko Ono debuted “Cut Piece” in Yamaichi Concert Hall Kyoto on July 20, 1964. It was then followed by her performance of the said piece in the same year at the Sogetsu Art Center, in Tokyo. “Cut Piece” was performed also in 1965 at the Carnegie Recital Hall in New York; in 1966 at the Africa Center, London; and the most recent one, in 2003, in Paris.

This work of art based on some analysis is said to be a protest against war. Specifically, the Hiroshima atomic bombing. The way Ono’s clothing is cut and torn resembles the clothing worn by Japanese citizens after the bombing. Her intention in having audience members take souvenirs home is to have this performance live on after she says her part is finished. There is optimism that members of the crowd will look at their slashed clothing, recall the turmoil triggered by war, and change their behavior to bring about peace.

This artwork is first and foremost one of the unique arts that we have encountered. It depicts such acts of bravery that a woman can do. From the past generations, women are kept in a cage of thought that they are not enough to do such things. But look how women can even overpower the men in today’s time. This art is not merely about the visuals that we normally see when there are exhibits. but it includes the participation of audiences. The art is not complete without the audiences. The cut pieces also raised its audience’s awareness as it was a form of protest against the war.

“Princess Urduja” by Fernando Amorsolo

“Princess Urduja” was painted in 1959 by Fernando Amorsolo, a Filipino portraitist and painter born on May 30, 1892. He was the first National Artist in the Philippines and is known as the “Grand Old Man of Philippine Art.” Known for their signature luminosity and ability to depict the iconic provincial Filipina, Amorsolo’s paintings typically portray scenes in glowing rural landscapes, such as farmers ankle-deep in rice fields, ladies in colorful baro’t sayas picking through mangoes, and vibrant society portraits.

Fernando Amorsolo also made several paintings, including portraits of prominent politicians, nudity, the dalagang Filipina, and a series of historical paintings on pre-colonial, Spanish colonial, and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during World War II. In the 1950s, Amorsolo created multiple paintings of Princess Urduja in his efforts to promote pre-Hispanic Filipino figures. However, most of the features of his portrayal, such as clothing and weaponry, came from Amorsolo’s imagination due to the lack of historical information on the Philippines in the 14th century.

Amorsolo’s Princess Urduja is a historical fantasy: The story began with the rise and prominence of the Shri-Visayan Empire in the 6th through the 13th centuries, and political dominance by conquests and wars occurred. The population of men decreases as a result of the series of wars. In time, due to the lack of available men, women eventually had to take the role of men on the battlefield, leading them to create the high art of combat in order to protect their political status. In the 14th century, Urduja, a queen of a matriarchal dynasty, ruled Tawalisi, in what is now known as Pangasinan. Princess Urduja had training in the art of combat when she was a young kid, and she eventually grew to be skilled in wielding a variety of weapons, including swords, spears, and bows. She was a well-known duelist as well as an expert navigator. The young, lovely, well-grounded Princess Urduja was known to be a good fighter who had personally led her warriors to the battlegrounds. Her warriors were women proficient in weaponry and horseback riding with well-developed bodies, tremendous strength, and masculine physiques known as Kinalakian, Kalakian, or Amazons. Princess Urduja led her kingdom to several triumphs in the war against kingdoms, pirates, and foreigners that threatened and opposed her territories during her reign. With her beauty and charm, Princess Urduja attracted several suitors; however, she declared that she would never wed a man who could not beat her in combat. Many men have attempted, but none have ever succeeded in doing so, and she has lived her whole life unmarried.

Filipino men and women in pre-colonial Philippines were already recognized as equals in society. Women were able to take on leadership positions. They were warriors battling alongside mankind. They were in charge of the home, controlled the finances, and were involved in business and industry. The norm was equal rights. Unfortunately, they are now something we must fight for and strive to accomplish once more. We cannot dispute that “Princess Urduja,” with its captivating tale of a bold, astute, and kind-hearted woman, is one of Fernando Amorsolo’s best masterpieces for this painting depicts a modern, powerful, and independent lady who is proof that women are just as competent as men and can become successful leaders. This painting serves as an inspiration for generations of women and a legendary symbol that we women are equal to men, and we have rights that need to be respected too.

“Timoclea Killing her rapist” by Elisabetta Sirani

335 BC is the date. Warfare has reached a lethal high point. The city of Thebes has been pillaged by Alexander the Great’s invading forces. The city is on the verge of extinction, and thousands of people will be forced into slavery. A woman named Timoclea is raped by a Thracian captain, who then has the audacity to ask her if she has any hidden money. She claims to, and leads him to a well, where she pushes him to his death and pelts him with stones from above. Alexander lets her get away with it because she has stories about a valiant, male relative of high status. Only the aftermath of the murder is depicted artistically until a 1629 engraving in order to portray Alexander as a figure of mercy. It is not until 1659 that an oil painting depicting Timoclea’s vengeance is unveiled.

It is the year 1638. Elisabetta Sirani is born into the world. She will be taught as an artist in her father’s studio, much to his frustration at first, but he can no longer deny the girl has talent. She will eventually take over his workshop and open an institute to teach female students. She will be her family’s breadwinner. She will die at the age of 27, most likely from a ruptured ulcer, but her maid will be charged with murder. Second only to utter conspiracy, 1665 Bologna loves a story of death by heartbreak, and rumors circulating.

We must consider how much of a self-insert the figure becomes through costume, and not just to the painter. This depiction of a clearly 17th-century woman engaged in vengeance provides a female viewer with a cathartic lens through which to view the violence she herself is likely to have experienced in an intensely patriarchal society. Although her skirts lack panniers, this stylised Timoclea reflects the feminine ideal of Sirani’s time, just as our beach-waved hair in period dramas reflects our own – rather than saying much about the 19th century, this stylistic choice reflects our own ideas about how women should or should not look. Timoclea wears a bodice that corresponds to the year she was painted, 1659, whereas her rapist costume corresponds to 330 BC.

She was inspired by an engraving by Matthäus Merian the elder, but she changed the compositional details. Merian stages the event in an elegant garden surrounded by a high wall that separates it from the city. He depicts the moment when a soldier’s body falls into the well without resistance, with the heroine only supporting his legs.

Plutarch claims that Thracian forces invaded Thebes in 338 BC. Timoclea, a resident of Thebes, was raped at her home by the captain of the Thracian forces. He then asked her if she knew where she could find money. She replied that she did, led the captain to a well in her garden, and informed him that there was money in the well. She gave him a good shove when he peered into it. She threw heavy stones until the captain died. Sirani turns patriarchy on its head, while the woman stands firm and determined despite being wronged so horribly.

As we chose our theme to be about feminism. This artwork is a perfect example of a strong female character. I chose this because Elisabetta Sirani perfectly illustrated how Timoclea is brave enough to defend herself with the means of killing the one who raped her. This artwork is an eye opener to many people as it teaches us to speak up, and fight back for ourselves.

“One Thousand Eggs For Women” by Sarah Lucas

“You’ve got to crack a few eggs for you to make an omelet” – quoted from Sarah Lucas. It is a recurring notion back in the historical times on how eggs have been used as fertile subjects by many art practitioners in a still life form. All of which were composed into one-lined ideology that “Justice hasn’t been done to the egg, neither to a fried one”. This thought persisted before Sarah Lucas’ Self Portrait with Two Fried Eggs back in 1996, where two sunny-side up eggs were placed across her breasts, creating one of the most iconic artist self-portraits of the few decades. Almost all of Lucas’ famous artworks involved the usage of eggs as subjects.

But this time Lucas made use of eggs in a sculptural work, of a grand scale staging, her participatory piece One Thousand Eggs: For Women in her exhibition of Au Naturel

This masterpiece, explicitly made use of no more or less 1000 eggs to be thrown on plain white gallery walls of the New Museum by women, as well as men that were requested to be dressed in drag or “giant phalluses”. The artist put emphasis that this artwork was not simply to make an art out of a mess but, it was about being really neat and making the most beautiful egg painting. This calls for a new motif and realization on the symbolism of the eggs that started from the Pagan fertility rite of egg throwing during spring. And was then adapted by Christians and reformed as Easter. This movement consequently defined Lucas’ career even more. Lucas’ themes of artwork revolved on ending stereotypes, women objectification, misogyny, and gender roles raised by the evolving human society.

One Thousand Eggs: For Women, had two previous installations back in 2018 at Berlin and Mexico. Both installations were staged during Easter in a manner of mirroring the medieval tradition of rebirth in spring. This artwork was a playful presentation of femininity and fertility held by women, and men who’s in full support for feminist movements. At the same time, it was a call for an opposing movement to pretension and limited women roles due to gender stereotypes. Alongside with Lucas’ naturally and personally conceptualized oeuvre, it digs deeper towards art historical traditions, wherein artists would mix pigments and egg yolk to advent for a quick-drying and long-lasting hue of color. This whole art piece, from its process of creation became a performance as well depicting the act of community and solidarity that banded people of the same beliefs together and brought them to the sense of liberalism and empowerment. Just like the yolk mixed with pigments before, this movement had a vivid hue of an act of public resistance which shall be remembered for decades.

Lucas’ tries to make use of this artwork to put the fate of each egg that a woman owns to her hands alone. It elucidated on the significance of respecting women’s rights over their own bodies. This was a step forward to topple down all limitations placed before the personal choices of women in their control of their own bodies.

Overall, I chose this artwork to play a significant role in this exhibition, for from a simple artistic gesture and idea Lucas had in mind she broke a conventional norm of women submissiveness. This was a big step of giving freedom and liberation to every participant, by giving them the choice of choosing the sort of mark they would want to make on the white walls. For once, these women felt they had the control for everything that they had and they could do anything they wanted to with their own strength. This was not simply an artwork, but a protest against the persisting irrelevant living norms that limits every woman in this world. It was a call for equality and unity. The bands that once tied women from living the real life, tied people together for a new and justified belief system. This was a polyvocal work that acted primarily as an instigator and served as the voices of the unheard, which was truly a work that we need in this contemporary.

“Though we have the courage to raise our daughters more like our sons, we’ve rarely had the courage to raise our sons like our daughters.”

Gloria Steinem

Authors:

Corpuz, Samantha

Lampa, Angeline

Sampang, Elaina Angelika

Sinio, Love Lyn

References:

Journal, D. A. (2022, November 16). The history of dance is feminist: The greatest female choreographers who changed the world of modern dance. dance art journal. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://danceartjournal.com/2020/03/07/the-history-of-dance-is-feminist-the-greatest-female-choreographers-who-changed-the-world-of-modern-dance/#:~:text=Another%20obligatory%20name%20of%20the,image%20of%20the%20female%20body.

Meet the mother of modern dance, Isadora Duncan. Isadora Duncan: The mother of modern dance. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://sites.barbican.org.uk/isadoraduncan/

Dance History: Isadora Duncan. The University of the Arts in Philadelphia . (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://uarts.digication.com/dance_history1/Career_1900_s

Isadora Duncan , Madre della Danza Moderna E Pioniera del Femminismo. Rome Central Magazine. (2020, October 26). Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.romecentral.com/en/isadora-duncan-madre-della-danza-moderna-e-pioniera-del-femminismo/

Passive objectification: Vulnerability in Yoko Ono’s participatory art. Passive Objectification: Vulnerability in Yoko Ono’s Participatory Art | Writing Program. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal/past-issues/issue-8/gallagher/

Yoko Ono Art, bio, ideas. The Art Story. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://www.theartstory.org/artist/ono-yoko/

Meg DiRuggiero, ’18. P. on D. 6. (2018, September 21). Yoko Ono’s “Cut piece”. Museum of Art. Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://www.bates.edu/museum/2017/12/06/yoko-onos-cut-piece/

Clark, J. (2022, June 3). PRINCESS URDUJA: Finding the legendary 14th-century Philippine heroine. The Aswang Project. https://www.aswangproject.com/princess-urduja/

Fernando Amorsolo. (2021, February 18). Ateneo Art Gallery. https://ateneoartgallery.com/artist/fernando-amorsolo

Baetiong, A. M. (n.d.). RCBC F. Amorsolo. Scribd. https://www.scribd.com/document/429797711/RCBC-F-Amorsolo Admin.

Elisabetta Sirani, Timoclea killing her rapist, 1659. Narrative Painting. Retrieved December 3, 2022, from https://narrativepainting.net/elisabetta-sirani-timoclea-killing-her-rapist-1659/

BadBride, B. B. (2020, July 5). Elisabetta Sirani and her image of timoclea, by Emer NÍ Fhoghlú. B A D B R I D E. Retrieved December 3, 2022, from https://www.badbride.com/bbbadies/elisabettasirani

Otulina. (2020, December 3). Power of women. Otulina. Retrieved December 3, 2022, from https://otulinablog.pl/en/2020/12/03/power-of-women/

McAloon, W. by J. (2020, April 21). Sarah Lucas got women to throw 1000 eggs at the wall. ELEPHANT. Retrieved from https://elephant.art/sarah-lucas-1000-eggs-for-women/

Phaidon. (n.d.). What is it with Sarah Lucas and eggs? PHAIDON. Retrieved from https://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2018/september/18/what-is-it-with-sarah-lucas-and-eggs/

Almino, E. W., & Rinehart, L. (2019, May 28). Why splattering eggs on a museum’s walls with other women was so satisfying. Hyperallergic. Retrieved from https://hyperallergic.com/502398/why-splattering-eggs-on-a-museums-walls-with-other-women-was-so-satisfying/

Leave a comment